I dropped to the floor in excruciating pain and curled up in a semi-fetal ball, the sensation of a red-hot pitchfork gyrating around my stomach like a blender of sulfuric acid.

My wife Suzy and I had just crossed the border into Argentina from Northern Chile and stopped at a roadside hotel for the night.

Although most nights thus far were spent camping, a nagging ache in my right side mandated a respite. She had stepped out to grab something to eat when it hit. I’ve never been a highly spiritual person, but the world became increasingly fuzzy and I’m pretty sure I reached out to the big man upstairs. Lying there alone in a cheap hotel room 6,000 miles from home, I wondered, Is this how I will die?

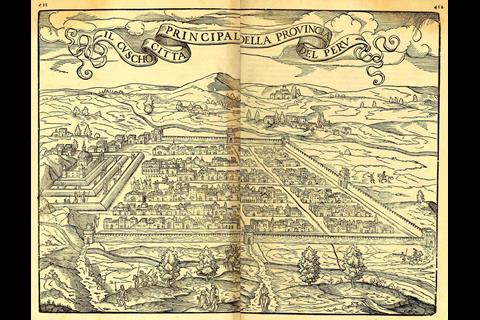

Ten days earlier we had landed in Cusco, Peru, after a 48-hour cascade of flight delays, cancellations and reroutes. The initial plan was to locate our Toyota 4Runner, explore the Incan ruins of Machu Picchu, then thread a path south to Chile and cross the Andes into Argentina.

The former was easy. I’d purchased the vehicle sight-unseen the prior year with my friend Christian Pelletier, with the agreement that we’d trade off using it for trips around the continent. Christian had driven it up from Santiago and left it at an overland camp in Cusco.

My modus operandi is to spend a day checking mechanical stuff like fluids, tires, brakes, lights and electrical, tools, and non-perishable stores. Packing the rig for the road, sourcing food and some touristy sightseeing will burn another.

This was my introduction to the 4Runner, and at first glance everything looked in order. It’s a 2001 SR5 with a 3.4-liter V6 mated to a slushbox transmission. Up top is a rooftent and storage box, and out back is a well-designed cabinet system with a swing-out table and ARB fridge-freezer. Electronics include dual batteries (one starter, one house), charge controller, a solar panel and inverter. I turned the key and she fired right up.

All good, but in South America, rather than requiring a costly carnet de passage (akin to a vehicle passport), countries grant a temporary import permit, or TIP. The duration depends on the country, 90 days in some but up to a year in others. Peru, however, only grants three months and ours was running short on breath.

During my years of travel I’ve learned that being flexible is paramount. Police and military checkpoints, disorganized border crossings, closed roads, crazy traffic jams and flight cancelations just happen, and getting bent out of shape solves nothing. Though I’d visited Machu Picchu in the ’90s, this would be Suzy’s first time. Unfortunately, an expired TIP es un problema grande, and the Lost City of the Inca was not in the cards. On to Plan B.

Lake Titicaca & Montezuma

Heading south towards the bustling town of Puno, we grabbed a room in a small hotel along Lake Titicaca. With an elevation of 12,500 feet, it is the world’s highest navigable body of water, and its shores are home to the indigenous Uros people. Celebrated for their floating reed island cities, which were designed as a movable and defensible space, the Uros historically referred to themselves as Lupihaques, or “Sons of the Sun.” We planned a tour and settled in for dinner and libation.

Around midnight, Suzy darted out of the room and down the stairs to the shared bathroom. Food poisoning. The human body is an amazing thing, and when it detects a vicious virus or bacteria it takes action. In the case of food poisoning, it promptly expels the buggers with a vengeance. Fortunately, it usually passes within 24 hours. She endured a miserable night worshiping the porcelain god, during which a major storm rolled in and foiled our plans for a lake excursion.

Sleeping most of the next day, she missed the spectacular drive to the town of Tarata. The Andes are the longest mountain range in the world, stretching 5,000 miles from the southern tip of Chile to Colombia. With an average height of 13,000 feet, lowland valleys might be 8,000 and passes might hit 14,000. The roads, however, don’t cut through mountains as they do in the U.S. Rather, they twist a serpentine path around every bend. Llamas and alpacas graze on the hillsides and pink flamingos peck around in streams.

Suzy was feeling better by the time we reached town, but the bug caught up with me and it was my turn to dance with good ol’ Montezuma. Unable to find a bathroom, I keeled over in the middle of the town’s square and promptly distributed the contents of my stomach all over my boots… while doing everything I could to not soil my britches. Ah, the joys of travel.

We were both on the upswing the following day when we reached the border and slinked into Chile—the final day of our TIP. Machu Picchu and the reed village were a bust, but we were feeling good and had 10 days before we needed to be in Buenos Aires. Tracing the coastline, we took a detour down a cliffside road to the 17th century village of Pisagua, which translates to “place of scarce water” in English. At first glance it appeared to be a sleepy fish camp, but the air was heavy with an unsettling vibe.

Boxed in by the ocean to the west and the Atacama Desert to the east, this desolate outpost was originally established to defend against pirates looting gold and silver from mines in Potosi and Oruro. But as late as the 1990s and the rule of dictator Augusto Pinochet it was used as a concentration camp for political dissidents, homosexuals, and anyone else that was out of favor. Big fish weren’t the only catch of the day, as bodies would regularly be pulled out of the bay and shallow graves were found in the hills. In my book, a bad vibe means it’s time to skedaddle.

Jewel of the Andes

Located near the border confluence of Bolivia and Argentina, San Pedro de Atacama is an oasis in the desert. Its earliest inhabitants, the Atacameños, predated the arrival of Columbus in the Americas and were revered for their woven baskets and pottery. Today it is a popular destination for day-tripping tourists and the last opportunity to grab fuel and supplies before crossing the Andes.

Camino Veintisiete (route 27) is one of the last all-dirt roads to Argentina and climbs 7,000 feet before reaching La Pacana, the largest caldera in the Altiplano-Puna volcano system. We took time to explore the glacial-blue lakes that dot the region, and some of the world’s best camp spots can be found by turning up any canyon.

Unlike the border crossings of the ’90s, when a long stretch of no-man’s land lay between confusing and unorganized immigration checkpoints, the process at Paso de Jama, now in a shared complex, is as seamless as checking out at Costco.

Finding a nice camp a few hours inside Argentina, which would normally involve dinner and a sundowner, we settled in for the night. But I wasn’t in the mood for anything but sleep. Since my gut-wrenching episode in Tarata, a gnawing ache remained on the right side of my stomach. Attributing it to a pulled muscle, I assumed it would work itself out over time and would tough it out. But it wasn’t subsiding.

I asked Suzy to drive the next morning, and when we gained cell service I called my friend Dr. Jon Solberg, an Army-trained surgeon and head of an ER department. After a barrage of questions, he suggested I might want to stay close to a town with a hospital. We headed for the traffic-choked city of Salta, and after an hour-long attempt to locate a parking spot near a pharmacy we decided to move on. After all, my situation did not seem life-threatening.

Morphine & Jesus

I was having a come-to-Jesus moment when the medics arrived. The minor annoyance had transformed to unbearable agony, as if demons were playing spin the bottle between my belly button and hip with a serrated pitchfork. They piled me onto a wooden slab in the back of a buckboard ambulance, and Jon’s words raced through my mind as we bounced across town to the clinic.

“Apéndice!” the nurse declared as she slid an ultrasound wand over my stomach, “Necesitas cirugía,” and then buried a needle deep in my shoulder. Ahhh, morphine… me like morphine. While our Spanglish is just enough to get by, medical terms are similar. My appendix had ruptured and needed to come out. We discussed options: four hours of backtracking or three toward Buenos Aires. I talked the nurse into another prick in my shoulder—one for the road—and we were on our way.

Arriving in Roque Sáenz Peña about 0430, the hospital staff was expecting us. Another ultrasound and I was introduced to Dr. Booth. He examined me and asked how long I’d had this pain in my stomach. My answer drew a furrowed brow and shrugged shoulders as if to say, “Did you think it would just go away, dummy?”

At this point I need to state that Argentina has two medical options, modern pay-to-play affairs, and a public system. The caveat with the public system is that it doesn’t quite hit the mark with regard to Western expectations. It is, however, gratis, even for wayward tourists. Humbling. While the staff was wonderful, but everything else was a bit shy of a baker’s dozen. My room lacked anything that resembled medical equipment, electrical plugs dangled from the wall on bare wires, and small sand dunes blew through the hallways.

You might ask why I didn’t move to a private facility? I’m not a medical expert, but given the news that a spewing appendix can kill you post haste, options were limited. I carry Redpoint medical evac insurance, and their team had gone into action discussing the situation with the staff, Suzy, and myself. The rep said, “We can get you to Atlanta in 24 hours, we can’t guarantee you have that much time.” It might not have been the Mayo Clinic, but it was a hospital and Dr. Booth seemed competent. I looked at Suzy and said, “We’re doing it here.”

A few hours later they slid me through a small window onto an awaiting gurney in the operating room. It was dark but looked fairly modern with many high-tech contraptions, blinking lights, and monitors. They stuck a needle in my back, an epidural, and I would be awake to witness their mastery of the craft. So far so good. That was, however, until a nurse opened a large book resembling a Chilton’s auto manual, poked at my stomach curiously, and said “aquí?”

Dr. Booth entered and gave me a reassuring nod. My mind raced. Are their tools sterilized, what if they forget one in my gut, how many appendectomies have they done, how many patients didn’t make it? What about post-surgery infection? Sepsis, which can send you to the morgue instead of home, is a common post-op issue. Only a few times in my life has it crossed my mind that this could be the end. I gave Dr. Booth a thumbs-up and out came the knife. An hour later, a small brownish-red organ resembling a mangled finger dangled in front of me on a pair of tweezers. Dr. Booth smiled: “Tu apéndice!”

Angels of Argentina

That evening two strangers entered my palatial quarters bearing gifts of food and water—which are the family’s responsibility in public hospitals. Suzy had contacted Christian, informing him of the situation and that we would not be dropping the 4Runner off in Buenos Aires as intended.

He reached out to his Argentinian friend Marcos, and through a Six Degrees to Kevin Bacon kind of way, Claudio and his wife appeared like guardian angels. In the coming week there would be others, Gaudi, Sergio, and Dolores, each appearing in our moment of need. Such is the tangled and interconnected world we live in. As the days unfolded, I expected Kevin Bacon to show up with a signed DVD of Footloose.

Mmmm, food, but not for me. I would be on a strict IV-only diet for five days. A minor inconvenience, so long as that bag kept pumping antibiotics into my veins. I suggested Suzy get a room, but she wanted to stay close and instead opted to sleep in the 4Runner or arm-wrestle a clan of cockroaches for space on the floor.

My release day arrived, but it was only a transfer to another cell block for five more days of observation. Considering a drain tube still dangled from my side, we didn’t have much of a choice. But Suzy had been sleeping in a metal chair or with bugs on the floor—we were getting a hotel room and would come back for daily checkups. Dolores booked us accommodation and, now free to ingest solid food, we proceeded to feast at a traditional Argentinean barbeque—I’d already begun gnawing on my socks for sustenance. Suzy also rebooked flights with Delta from Buenos Aires to the States, just in case.

“Arhhagryaa,” I bemoaned as the nurse yanked, without warning, the 18-inch hose out of my side during our first follow-up. It must have been wrapped around my larynx and left lung, as I could feel it being dragged through my body on its way to freedom. As it flopped onto my stomach, I looked at Suzy and mouthed, “We’re getting on that plane.” The next three days were a blur.

Guadi arranged for us to store our vehicle at their business in Resistencia, and the next morning we made the 100-mile drive to meet our guardian angels. Dolores fed us lunch, helped us book a flight to Buenos Aires, and Claudio’s father-in-law had his attorney draft an affidavit for a third party to drive our 4Runner in our absence. We offered to pay for storage, their gracious assistance and legal fees, to no avail.

Guadi and Dolores drove us to the airport that night, where we sipped tea and got to know each other. Apparently, years ago Dolores and her husband were in San Diego seeking medical care for their son. The treatment took more time and money than expected and they found themselves in a strange land, broke, and with an ailing son. In their moment of despair, her angels materialized. A family took them in and provided for their needs, and we had become her opportunity to return the gift of goodwill.

As we settled into our seats and the flight attendant secured the door, I contemplated the degrees of separation between any of us and the one individual amongst billions that might change the course of our lives. Be it the Erdős-Bacon effect, an underpaid surgeon in a public hospital or angels from Argentina, our world is a better place.

As for my appendix, it’s one less thing I’ll need to worry about on my next adventure.

Access More Great Stories!

This article originally appeared in OVR Issue 08. For more informative articles like this, consider subscribing to OVR Magazine in print or digital versions here. You can also find the print edition of OVR at your local newsstand by using our Magazine Finder.

No comments yet